Jeff Finely

Light + Life Executive Editor

Jeff Finley is this magazine’s executive editor. He joined the Light+Life team in 2011 after a dozen years of reporting and editing for Sun-Times Media. He is a member of John Wesley Free Methodist Church where his wife, Jen, serves as the lead pastor.

by Jeff Finley

The editor of this magazine visits a Chicago park and gets caught in the middle of a heated confrontation between police officers, members of the National Socialist Party of America (a neo-Nazi group), a Black teenager, and other protestors.

“Threats and obscenities fill the air,” reports the editor who adds that he sees “racial hatred that far outstrips anything I witnessed” during a trip to apartheid-era South Africa. “I feel fear.”

This may sound like a recent news report, but the year is 1978, not 2020. Editor G. Roger Schoenhals goes on to write about the challenges faced by the nearby Free Methodist congregation in a predominantly white urban neighborhood known for trying to keep out minorities:

“So what should the people of the Westlawn Free Methodist Church do? If they allow Blacks into their fellowship — or even perform a wedding involving Blacks — the community will express vengeance upon property and person. (This happened one year ago.) Some in the church feel strongly that they should not minister to Blacks lest they jeopardize opportunities for ministry to the community.”

Schoenhals’ account of some church members’ acquiescence to racism may seem shocking in a denominational magazine — especially a denomination with an abolitionist heritage. The story doesn’t end there, however.

“The minority — including Pastor John Owen — take the position that a conciliatory [to racist neighbors] posture is contrary to the spirit of Christ. They want to take a stand no matter what the cost.”

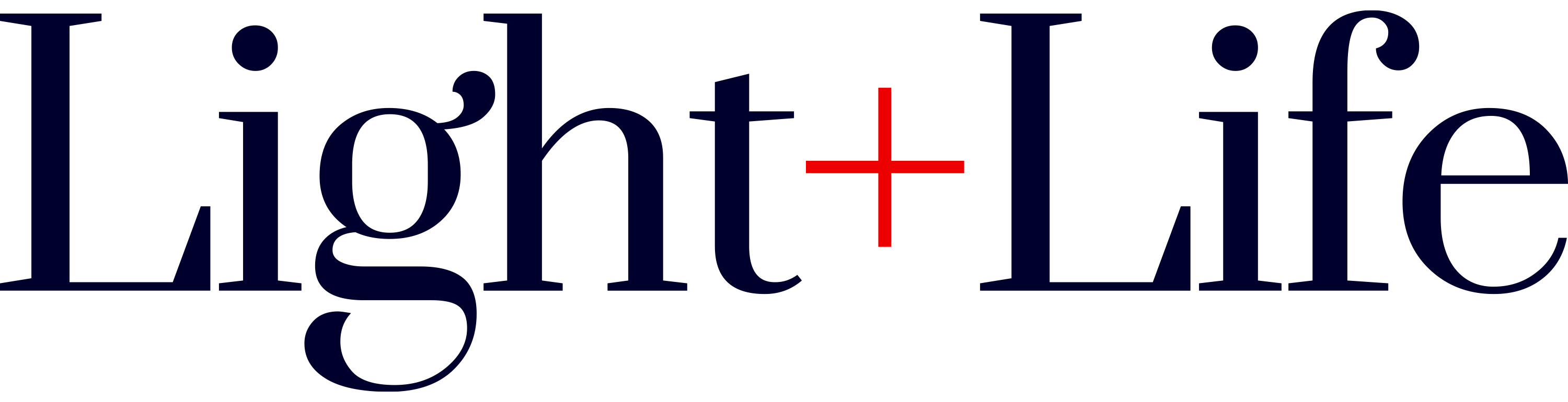

That pastor, John “Ike” Owen, only stayed for two years at the Westlawn FMC whose members had been threatened with firebombing (not an idle threat because the home of a local Salvation Army leader was firebombed) if the church continued its cross-cultural ministry efforts. After Owen’s removal, the church eventually closed.

“It closed because the church couldn’t come to grips with ministering to people of color,” said Owen, now the founder and executive director of the Crisis Chaplain Corps, during a September 2020 interview with LIGHT + LIFE. “I eventually was regarded as a troublemaker because I performed the wedding of a Black woman and a White police officer.”

That wedding fits with two recurring aspects of Owen’s more than a half-century of pastoral ministry — serving urban residents of color and also police officers (some of whom, of course, are police officers of color). E. Dean Cook’s book, “Chaplaincy: Being God’s Presence in Closed Communities” describes Owen as “one of the church’s pioneer police chaplains. His large frame and big heart have left a legacy of police and crisis ministry work across many states and cities.”

At an age where many people settle into retirement, Owen continues to follow God’s leading to serve urban residents and police officers. The night before his interview with this magazine, Owen unexpectedly served as a liaison between his immigrant neighbors and police.

Owen’s Chicago ministry was preceded by his time as a Free Methodist pastor in Minneapolis where he worked with people of multiple ethnicities while also serving as a chaplain for both the local Police Department and Minnesota’s largest mental health care facility. His chaplain work with the Twin Cities’ diverse residents attracted some of those same people to the First Free Methodist Church — not only African Americans but also many Latinos and Native Americans. Owen noted that Minneapolis is among the North American cities with the highest number of Native American residents.

During protests three days after the death of George Floyd, the Minneapolis Police Department’s 3rd Precinct station was burned down May 28.

“The 3rd Precinct is where I got my start in the police chaplain ministries in the late ’60s,” said Owen, who worked with the area’s diverse residents and helped the department recruit African American and Native American chaplains. “You can’t be involved as a police chaplain without encountering all of the cultural aspects of our country.”

Rural to Urban

Owen said he has been given “an apostolic gift” to be able “to jump cultures.” He said he was “raised in a hollow in Appalachia on a crick [creek] bank with an outhouse and went to a one-room school, so you couldn’t be more rural than I was.”

He attended the Elmira (New York) Free Methodist Church, now known as Hand in Hand FMC, and he and his brother, Jim Owen, became friends with future Bishop Richard Snyder and his brother, Vernon Snyder. They formed a teen singing group and then went to Roberts Wesleyan College. He continued his studies at Asbury Theological Seminary in rural Kentucky. He was mentored by Gilbert James, a Free Methodist professor, who took some of his Asbury students in 1967 on a trip to Chicago where James gave the students different assignments.

“He assigned me to ride with police. I didn’t have a lot of interest in police necessarily,” Owen recalled. “I saw unbelievable corruption exercised on the South Side of Chicago.”

Among other things, he witnessed tavern owners and businessmen giving cash bribes and alcohol to police, who also had ties to prostitutes.

“I couldn’t believe what I was experiencing,” Owen said. “I said to the Lord, ‘If you ever give me a chance to have anything to do with addressing police corruption, I’d like to be able to do that.’”

Owen said that as he graduated seminary, “I knew I was called to urban ministry, but I was supposed to go back here to New York to serve.” However, doors closed in his home conference to urban ministry opportunities, “and in the providence of God, He called us to Minneapolis.”

His wife, Belva, worked either 3–11 p.m. or 11 p.m.–7 a.m. shifts as a Veterans Affairs nurse, and the young pastor decided that as “my [church] people went to bed, that’s when the city came alive.” He would watch television reports of nighttime crime and think, “Who is with these people who are suffering these experiences of domestic abuse or shootings or fires? … Who’s winning them to Jesus?”

He started by carrying a portable police scanner in his car and heading to the sites of police calls. Owen one night delivered cake and tea to the 3rd Precinct police station. No officer wanted to touch the cake or tea until one older lieutenant finally said, “Come on in, John. I’ll eat some of your cake.” Owen later learned the officers previously were the victims of a cake spiked with a laxative.

“I learned from that experience that they’re just like us; they have to trust you. That began my involvement with them, and pretty soon they started asking me to ride with them,” said Owen, whose first Minneapolis ride-along was with a Black officer and his White partner.

The chaplaincy program took off, and Owen’s efforts were documented as part of the book “Miracle at City Hall” by Al Palmquist with Kay Nelson. The Minneapolis program became the model for police chaplain programs across the country. Owen traveled in 1973 to Washington, D.C., to meet with other chaplains for the founding of the International Conference of Police Chaplains that he served as its first treasurer.

The following year, Owen was one of the urban pastors who participated in the Free Methodist Church’s first Continental Urban Exchange (CUE) at the International Friendship House in Winona Lake, Indiana, where the denomination had its headquarters at the time. He credited the efforts of Charles Kingsley, then the director of the denomination’s Christian Witness Crusades, who “in all of his travels found us urban pastors. He knew what we were doing. He knew that we were living out the gospel. He saw us in our context.”

He became a regular participant in future CUE gatherings that eventually led to the formation of the Free Methodist Urban Fellowship. Owen acknowledged that he and the other urban pastors didn’t always see eye to eye with denominational leaders, such as when a list named the “top 10 churches,” which primarily were located near the denomination’s colleges and universities. Owen explained, “We said it’s absolutely reversed. The top 10 churches are in Buffalo and in Minneapolis and in Chicago and in all these places where nobody recognizes them as the authentic church. We’re multiethnic. We’re multicultural. We’re primarily focused on the poor — not the rich and highly educated.”

Owen, of course, isn’t opposed to the churches near educational institutions. In fact, he served for a year as an associate pastor for youth and families at the First Free Methodist Church next to Seattle Pacific University. He said with a laugh, “I was the oldest youth pastor the congregation ever had.” He emphasized intergenerational connections and outreach to local schools and the Union Gospel Mission.

Capital Calling

After serving as a pastor in Buffalo, New York, Owen found himself without a church appointment, and he became the chaplain for the Erie County Sheriff’s Office. Meanwhile, he became increasingly burdened that Free Methodist ministry had ceased within the nation’s capital.

“Instead of following through with what we were called by B.T. Roberts and the Lord Jesus Christ, to reach the oppressed and the different, we took off and we left,” he said.

The Owens moved to Washington, D.C., in 1997 to begin a chaplain ministry that would revive Free Methodist outreach in the capital city. They were able to rent a house (which they later bought) in a predominantly Black neighborhood from Hubert T. Bell, an African American man who served as an assistant director of the U.S. Secret Service and later as the inspector general of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

A mutual friend recommended Owen contact Lloyd John Ogilvie, who served as the chaplain of the U.S. Senate. Owen met with Ogilvie who asked how he could pray for him, and Owen replied that he needed an office.

“He prayed with me that God would give me an office. The next day I get a phone call from the United Methodist Church saying, ‘We’re giving you the top floor of the United Methodist Building,’” Owen said. “God just did wonderful things to open doors.”

The United Methodists allow several other denominations to use space in the building. Owen had complimentary use of an office suite overlooking the U.S. Supreme Court plaza and the U.S. Capitol. He befriended the officers protecting the Supreme Court and the Capitol Building. When a Supreme Court police officer died unexpectedly, another officer asked if Owen could serve as the chaplain for the court police officers.

“They didn’t even ask me. They just made me their chaplain, so I met with Chief Justice Rehnquist, told him what I was doing, and he said, ‘Good,’” said Owen, who had sidewalk conversations with another Supreme Court justice and members of Congress — some of whom had apartments in the United Methodist complex. “But I wasn’t called there to minister to them. I was called to minister to the people that the police encountered — the voiceless, powerless people.”

When he arrived in D.C., only two of the capital’s multiple law enforcement agencies had chaplains, but Owen said, “God allowed others to get involved, and He helped use me to do it.” The different agencies now have their own chaplains.

He saw ministry opportunities decrease as security restrictions increased after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. In 2003, the Owens returned to New York where he provided chaplain services to the New York State Police.

At General Conference 2019, Owen received the Chaplain Medallion Award in recognition of 55 years of ministry as a pastor and police/crisis chaplain.

Whether preaching in the pulpit or sharing the gospel with protestors outside the Supreme Court, Owen has followed God’s call to serve our nation’s cities.

“I believe I am and was called of God to be an urban pastor,” Owen said. “All of the places I’ve been sent by God in the church are places that are in crisis.”+

Jeff Finley

Light+Life Executive Editor

Jeff Finley is this magazine’s executive editor. He joined the Light+Life team in 2011 after a dozen years of reporting and editing for Sun-Times Media. He is a member of John Wesley Free Methodist Church where his wife, Jen, serves as the lead pastor.